Redirecting X sessions

Running it here displaying it there

Back in the old days, where terminals were dummy and operators were not so nice to users, X was not a very popular generation of Macintosh operating systems, but rather a windowing system for UNIX and friends.

Without getting into troublesome detail, the windowing system cares for basic operativity in a GUI environment, things like drawing and moving program windows, handling the mouse and keyboard input. On top of it you have much more, the look and feel for example - but that is a matter for the window managers and desktop environments (KDE, Gnome etc).

The X Window System has stopped at version 11 in 1987, which would sound disappointing to the agile and fast releaser in you - but well if you get something very right, there is no need to change it… right?

11 is actually the version of the reference protocol and it is pretty advanced. Among other things, it allows for a decoupling between the component providing the windowing service - the X server - and the programs asking for windows to be drawn and clicks to be fired - the client applications. Furthermore, X uses TCP networking.

Do you see it already? Nothing prevents you from running some graphical program in the cloud but “use” it in the comfort of your little laptop. We don’t want to go that far maybe but let’s see how we can do something useful with the so called X redirection.

Why do you even want to do this

First of all, X redirection is so Linuxey and so ninetys, thus cool in its own. That kind of trick you learned at the local Linux Users Group as a kid, or used to impress your Windows-only peers at school - again, past times in this world of Linux-in-Windows and Docker.

But actually, there are a handful of cases where it is really useful. For example: you have a Linux box but the box is actually very old, so old and unstable that even running a low-carb desktop environment as XFCE is challenging. As the next stop would be to run a bare X itself - not very eyecandish and useful - you think of the following: why not borrowing some power from a new shiny Mac? Don’t panic if you don’t have such exotic needs - I had and it makes a good example for this post.

From Linux to macOs

Our dear osx laptop is a unix-like system and you know it. Thing is, its window server, represented by the obscure WindowServer process, does not speak X11 - and an X11 implementation is not included by default either.

No worries: you can install XQuartz - which is an independent project supported by them. So basically what we are doing is running our own X11 server on the powerful mac, and have the client applications on our Linux box use it as server: things will run on Linux but windows will pop up on the mac - magic.

Disclaimer: such a simple setup is OK for home but it should not be intended for real and secure use. In particular, the session is not encrypted, which means that traffic between the server and the client - keystrokes too - may be sniffed; for the un*x lamer in you, check this. The most common way to have such traffic encrypted is tunnel it via SSH.

Steps

We assume that the laptop and the box see each other eg they sit on the same home network.

When you open XQuartz you will not see anything but the server will start.

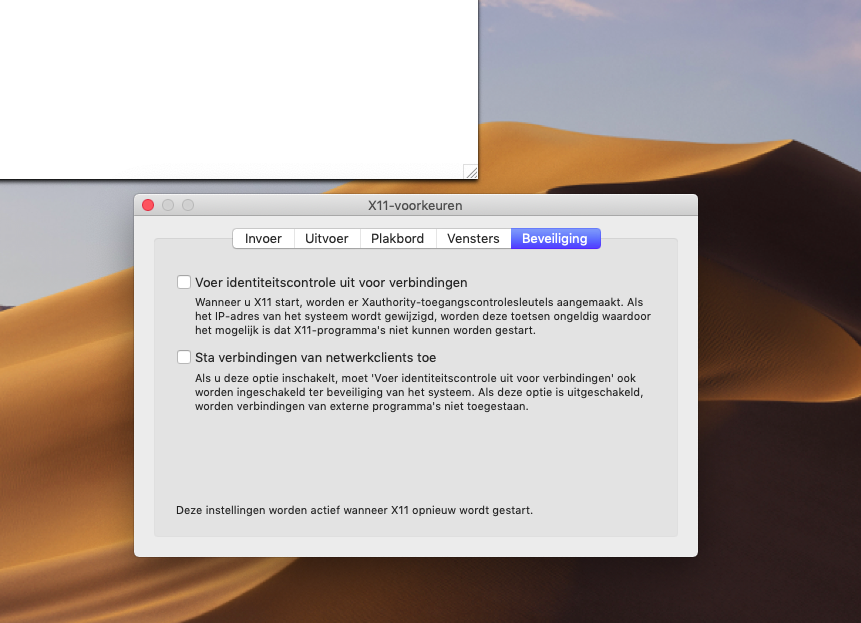

By default, at least in recent XQuartz versions, over-the-wire TCP will be disabled; to turn it on:

sudo defaults write org.macosforge.xquartz.X11 nolisten_tcp 0

so we are actually disabling the non-listening (you can actually set this in the program configuration too); check it is listening with:

netstat -na | grep 6000

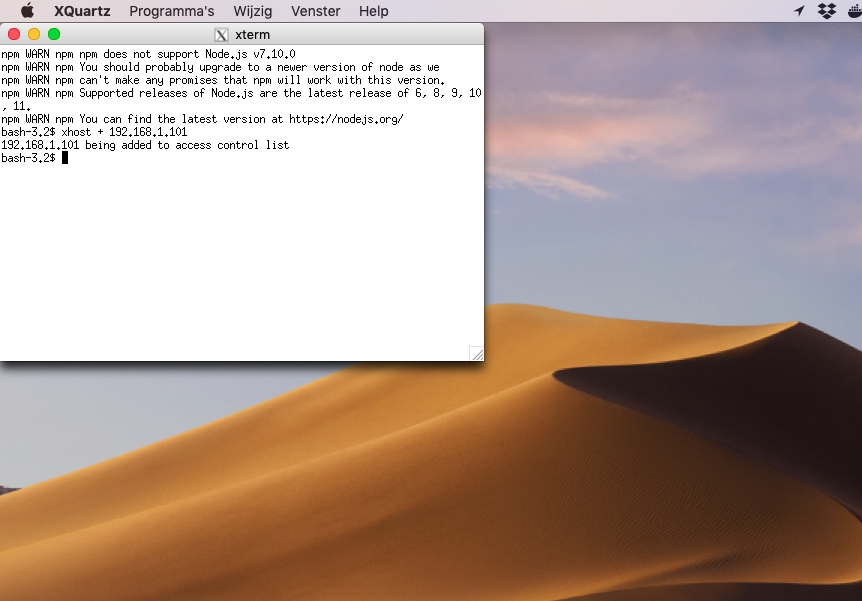

Then, we want to allow incoming traffic from a specific IP only; open a Terminal session, this time from XQuartz itself, and give:

xhost + 192.168.1.101

where 192.. is the IP of the Linux box. If you omit the argument address or hostname, any client will be allowed; using a minus sign removes a specific client or blocks all.

The host-based access is to be frowned upon because it not that secure, for example the request might be coming from an accepted router but be originating on some unwanted computer behind it. Completely fine for our test but keep in mind that a more secure approach - more secure in 80’s terms at least - is the cookie-based access via the .Xauthority file: for a program to be accepted by the remote server this file must be dropped in the user home of the user starting the program. How you upload it that is your business, for example scp.

On the Linux box, we want to configure the server display properly. Give:

export DISPLAY=192.168.1.103:0

where this 192.. is the mac IP instead (we are connecting to the first and only display server).

X-based applications on your Linux box, such as some new shiny release of XBill will now hook up to the configured remote server, so you can use them on the mac. To easily test you can try either:

xeyes

xeyes -display 192.168.1.103:0

I find it handy to launch programs in the background:

xeyes&

Be aware that if the connection drops most probably the session will die too, leaving a behaded program. Also if the network changes things break too. The legend goes that only a very rare binary of emacs compiled with X support by Richard Stallman himself, on gcc v0.5 has the ability to switch around sessions.

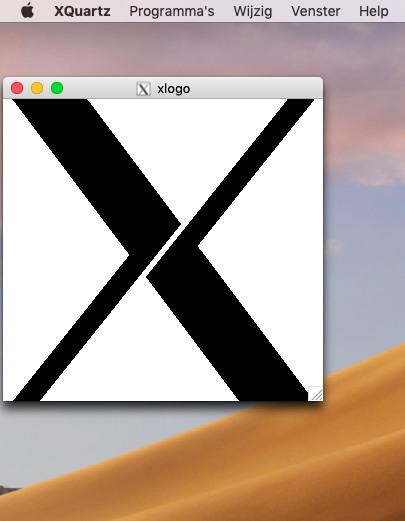

xlogo is another superb application I challenge you to test.

Anyways, congratulations, it is 1988 again!

Wasn’t that fun?

It never ceases to amaze how computers and all that go extremely fast, still things conceived and written so far away still work with little to no changes - by the way, do you know how old is ping?

In theory, it is also possible to X-stream videos and all that, but it will most probably hiccup and freeze.

Happy X-ing!